Timoshenko Beam#

Strong form equations#

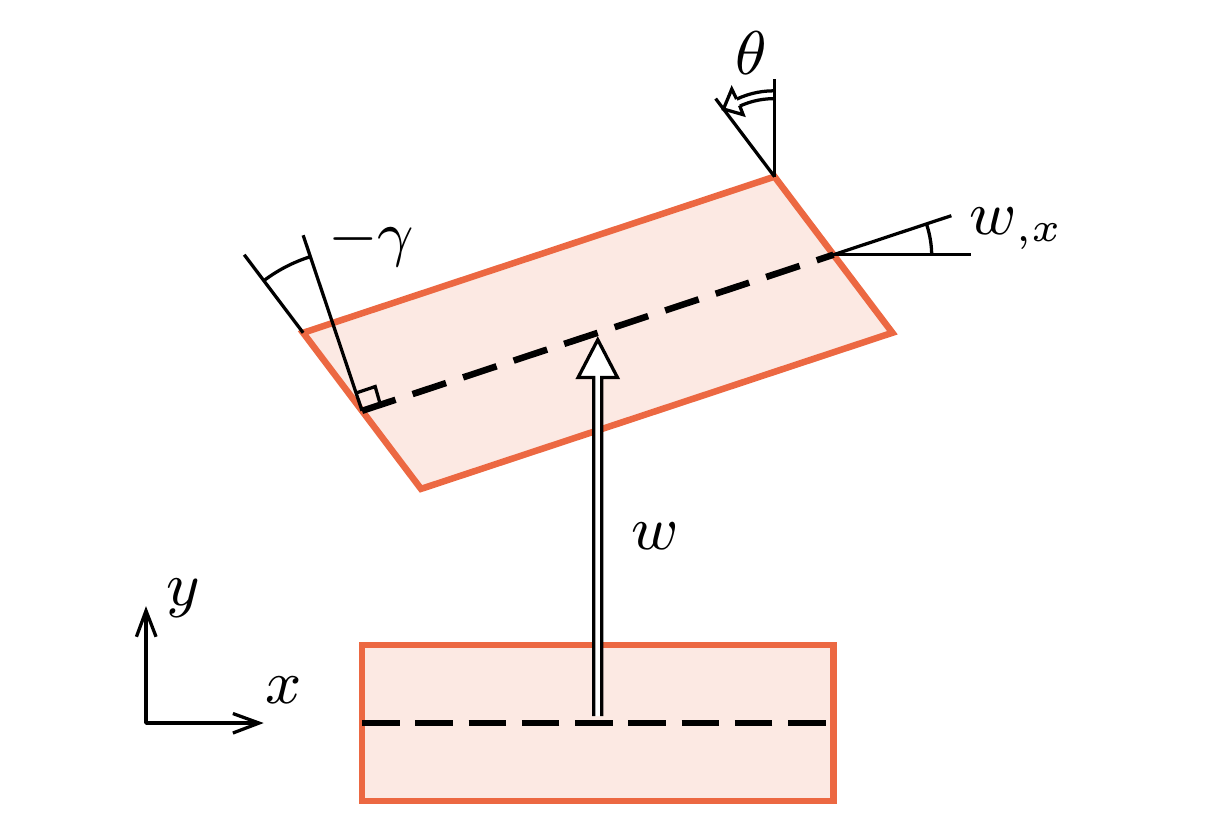

The Timoshenko beam allows shear deformation and is valid for slender as well as for relatively short beams. In Timoshenko beam theory, planes normal to the beam axis remain plain but do not necessarily remain normal to the longitudinal axis. In other words, the rotation of the normal to the beam axis \(\theta\) is not directly coupled to the first derivative of the deflection \(\frac{dw}{dx}\). This assumption allows for shear deformation, where the shear strain \(\gamma\) is a measure for how much the rotation of the plane normal to the beam axis with respect to the rotation of the beam axis itself. This is the first kinematic relation in Timoshenko beam theory:

Kinematics of a Timoshenko beam#

Is it apparent from Equation () that assuming \(\gamma\) to be equal to 0 implies a direct relation between \(w\) and \(\theta\) after which and only one unknown field remains: when \(w(x)\) is known, \(\theta\) follows, as is the case in the Euler-Bernouilli beam theory. In Timoshenko beam theory, however this is not the case. Shear deformation can be unequal to zero, and as a consequence \(w\) and \(\theta\) are independent fields. The two fields are coupled through the shear stiffness, but in the finite element formulation they will give rise to separate ‘independent’ degrees of freedom.

The second kinematic relation is the one that defines the curvature. This is defined as the spatial derivative of \(\theta\):

Each strain-like quantity is related to a stress like quantity with a constitutive relation. For linear elastic response, these are

and

where \(EI\) and \(GA_s\) combine material and geometric about the cross-section, and \(GA_s\) accounts for uneven shear stress distribution through the effective shear area \(A_s\).

Finally, there are two equilibrium relations, one for rotational equilbrium

and one for translational equilibrium (in \(y\)-direction):

where \(f_y\) is a distributed load.

Substitution of kinematic and constitutive relations in the equilibrium equations give the strong form equations for the Timoshenko beam:

which are two coupled second-order equations, over the domain \(\Omega\). To formulate a well-posed problem, two boundary conditions are needed at each end of the domain, either moment or rotation needs to be prescribed, and either the deflection or the shear force.

Derivation of the weak form#

This problem differs from earlier problems in the sense that we have a two strong form equations. In order to derive a weak form, we need to multiply each of these with a weight function and integrate over the domain. We will use different symbols and let the choice of symbols be inspired by the type of equilibrium that they represent. The first, Equation () came from rotational equilibrium, and we will use the symbol for rotation with a bar, so \(\bar{\theta}\) for the weight function.

The second, Equation () came from vertical equilibrium, and we use a symbol associated with the one for vertical displacements, \(\bar{w}\):

Applying integrations by parts one terms with second derivatives gives:

and then inserting the Neumann boundary conditions yields the weak form for a Timoshenko beam: find \(w \in S_w\) and \(\theta \in S_{\theta}\) such that

A more precise definition of the necessary functions spaces should be provided to complete the problem.

\(\newcommand{\bA}{\mathbf{A}}\) \(\newcommand{\bB}{\mathbf{B}}\)

Discrete Form#

The Galerkin problem for the Timoshenko beam involves finding \( w^h ∈ S_w^h \) and \( \theta ^h ∈ S_\theta^h \) such that

Representating the fields \(w^h\) and \(\theta^h\) and corresponding derivatives in terms of shape functions and nodal variables, we can write:

where we leave open the option of using different shape functions for the two fields \(w\) and \(\theta\). For the discretization of weight functions, we will use \(\mathbf{N}_w\) also for \(\bar{w}\) and \(\mathbf{N}_\theta\) also for \(\bar{\theta}\).

This may seem an arbitrary choice here. One thing that can be said in support of this choice is that it will ensure that the stiffness matrix is square and symmetric. A more physical argument in favor of this choice can be made when the finite element equations are derived from a virtual work equation instead of through the strong-form/weak-form recipe that we follow here.

Inserting the expressions for the unknown fields in terms of nodal variables and variations into Equations () and () and elimination of \(\mathbf{c}_w\) and \(\mathbf{c}_\theta\) leads to:

This can be summarized as a single system of equations as:

where the components of the the element stiffness matrix are given by

and components of the element RHS vector are given by

The resulting system of equations is symmetric. Can you make the argument why?

Solution

The stiffness matrix \(\mathbf{K}\) is symmetric if \(\mathbf{K}^T=\mathbf{K}\). For the block matrix of Equation (), this is the case if diagonal blocks are themselves symetric and if the off-diagonal blocks are each-other’s transpose, so if

\(\mathbf{K}_{\theta\theta} = \mathbf{K}_{\theta\theta}^T\)

\(\mathbf{K}_{ww} = \mathbf{K}_{ww}^T\)

\(\mathbf{K}_{\theta w} = \mathbf{K}_{w\theta}^T\)

That each of these three conditions is satisfied follows from the rule that for a matrix that the transpose of a matrix that is a product of two matrices is defined as \((\bA\bB)^T=(\bB^T\bA^T)\). The diagonal blocks have only terms that are defined as \(\bA^T\bA\); matrices of this form will always be symmetric because

The off-diaginal blocks themselves are not symmetric, but are indeed each other’s transpose as can be shown with the same rule:

The scalar factors \(EI\) and \(GA_s\) that appear in the stiffness matrix expressions do not affect the symmetry

Shear locking#

An important aspect of the performance of Timoshenko beam elements is the concept of shear locking. The Timoshenko element formulation derived above behaves overly stiff when loaded in bending.

Note

Shear locking is the effect that occurs in finite elments in which shear contribution to the energy does not vanish when they are deformed in pure bending, resulting in an overly stiff response with bending displacements that are smaller than they should be. The discretization error that appears in elements that suffer from shear locking vanishes extremely slowly upon mesh-refinement. Elements that suffer from shear locking are quadrilateral solid elements (particularly the 4-node version) and Timoshenko beam elements.

Consider a two-node Timoshenko beam of length \(L\), with the same linear shape functions for displacement \(w\) and rotation \(\theta\). The components of the stiffness matrix are given by:

Therefore, the stiffness matrix is of the form

If the one end of the element (node 1) is fixed, so that \(w_1=\theta_1=0\) and a shear load \(F_y\) is applied at the other end (node 2), the resulting two-degree-of-freedom problem is:

Finally, the solution for the displacement \(w_2\) is

Two limit states can now be identified:

For \(L \rightarrow 0\) : \( w_2 \approx \frac {PL}{GA_s} \)

For \(L \rightarrow \infty\) : \( w_2 \approx \frac {4 PL}{G A_s} \)

The shear-dominated response for \(L\rightarrow0\) is the exact solution for a shear beam. The slender limit of \(L\rightarrow\infty\), however, is not correct. For finite \(EI\) and \(GA_s\), at \(L\rightarrow\infty\), the beam response should be bending-dominated and the classical cantilever beam solution \(w=\frac{PL^3}{3EI}\) should be obtained. Even with an extremely fine mesh, this element will exhibit a very stiff response.

The stiffness matrix above can be obtained by analytical evaluation of the integrals in the element stiffness definition, or by using 2-point Gauss integration. For the case of one-point numerical integration, the integrals are not evaluated exaclty, but it turns out that this helps to remove the locking. With a single integration point at the center of the element, the stiffness matrix becomes:

Now, for the load case of a single element, fixed at one end, the displacement is given as:

And the limit states change as follows:

For \(L \rightarrow 0\) : \( w_2 \approx \frac {PL}{GA_s} \)

For \(L \rightarrow \infty\) : \( w_2 \approx \frac {PL^3}{4EI} \)

It can be observed that the shear beam limit is still exact while the nature of the slender beam limit solution is completely change. While it was incorrectly dominated by \(GA_s\) before, it now only has \(EI\), it looks very much like the classical beam solution, except that the factor \(\frac13\) from the exact solution is \(\frac14\) in the finite element solution. This difference is due to the fact that we are analyzing a cantilever beam with linearly varying moment with a single finite element. A single finite element is not enough to describe this scenario exactly, but if we would refine the mesh, the solution would approach the exact solution quite quickly. Below the finite element implementation is performed and the convergence for 2- and 1-point Gauss integration illustrated.

Uniform or selective reduced integration

Upon closer inspection of the element, it can be shown that the element performance improves if the shear terms those that have \(GA_s\) inside them are under-integrated with a single integration point. Coincidentally, the only term in the stiffness matrix that needed two integration points in the first place is the \(\mathbf{N}^TGA_s\mathbf{N}\)-term in \(\mathbf{K}_{\theta\theta}\). The \(EI\)-related term in \(\mathbf{K}_{\theta\theta}\) needs only one integration point to be integrated exactly. As a consequence complete under-integration does not give rise to new problems. This is different from the 4-node quadrilateral element, where under-integration also removes shear locking but causes so-called hour-glassing. To get a well-behaved locking-free 4-node element, selective reduced integration needs to be applied, where shear terms are integrated differently from other terms. The Timoshenko beam element, uniform reduced integration is a solution to the problem without side-effects.

An alternative solution is to use different orders of interpolation. An element with quadratic shape functions for \(w\) and linear shape functions for \(\theta\) does not suffer from shear locking even when fully integrated.