3.1. Geology#

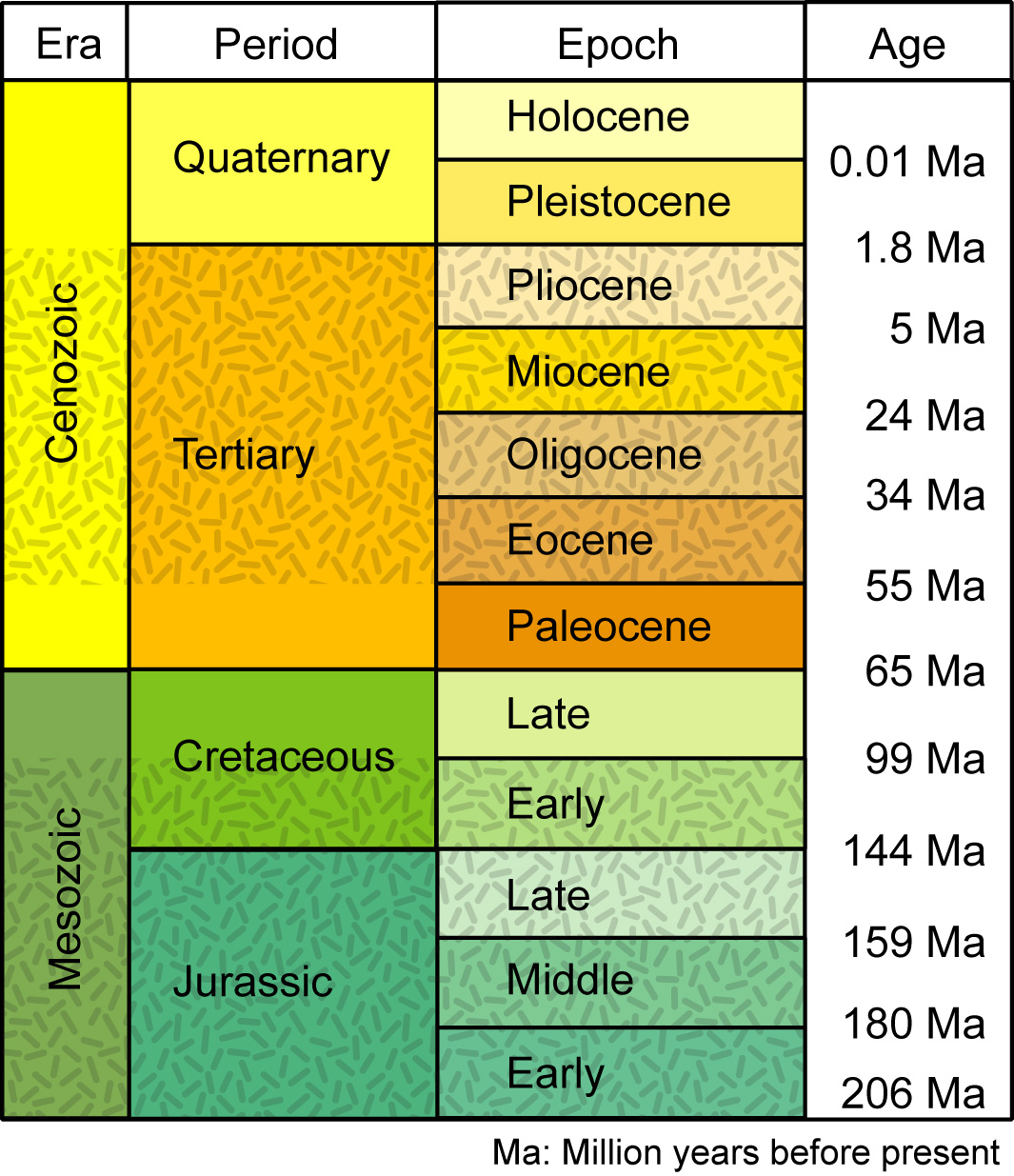

In the Netherlands, mainly the geological layers of the Quaternary are at the surface. The older layers from the Tertiary are located at greater depths; only in the south and east, they emerge at some places (Geologie van Nederland, n.d.). The marine clay layers from the Tertiary lie at approximately 400 meters depth and form the impermeable base of the aquifers. The Quaternary consists of the Pleistocene, which began between two and three million years ago, and the Holocene, which followed the Pleistocene and began only 10,000 years ago (see Fig. 3.2, (USGS, 2019)). DINOloket could be used to see what layers are present at a specific location in the Netherlands.

Fig. 3.2 Geologic time scale from the Jurassic Period to the present day. Stippled patterns indicate long segments of geologic time not represented by deposits in the Grand Strand region (that is, times of erosion or nondeposition). Simplified from Geological Society of America (1999) – data from (USGS, 2019).#

3.1.1. Pleistocene#

During the first hundreds of thousands of years of the Pleistocene, the Netherlands was still covered by the sea, and large amounts of marine sediments were deposited. Later, large rivers from the south (Rhine, Meuse and Scheldt) and subsequently disappeared rivers from the east, deposited sediments on the emerging land. Sand had the largest share in these continental deposits. These sand layers have a high porosity and are very well-permeable, which is why they are called aquifers. These aquifers are separated, among others, by poorly permeable sand layers deposited by the Rhine and impermeable clay, which was transported by the ice from Scandinavia during different ice ages.

The penultimate ice age had the greatest impact on the geology of the Netherlands. The ice cap formed tongues that pushed away the soil and created so-called tunnel valleys, which were surrounded by upthrust land, the push moraines. The highest push moraine, located on the eastern Veluwe, has an elevation of 100 meters +NAP (Dutch Ordnance Datum). The ice also deposited a lot of boulder clay (NL: keileem), which is difficult to erode and has been used since the construction of the Afsluitdijk to build dikes. Where the boulder clay is upthrust, such as on Texel and Wieringen, it forms a natural defense against seawater.

During the last ice age, the ice did not reach the Netherlands, but the subsurface was permanently frozen. During this ice age, the land was sparsely vegetated, and large amounts of sand were transported by the wind (so-called eolian deposits). The sand covered the old deposits and is therefore called cover sand (NL: dekzand). Almost the entire east and south were covered by this sand. In the South Limburg hilly region, finer dusty material was deposited by the wind, known as loess. The Pleistocene is only found at the surface in the east and south, while in the west and north, there are deposits from the Holocene on top.

3.1.2. Holocene#

After the last ice age, about 10,000 years ago, a warmer period began, known as the Holocene. In the Holocene, peat formed extensively as the conditions in the Netherlands were ideal for it. In wet and moist environments with moderate temperatures, the decomposition of dead plants is inhibited. Accumulation of these undecomposed plant remains leads to the formation of peat. A high groundwater level then causes the peat to grow rapidly. Peat that forms from plant remains in contact with groundwater is called “low peat” (NL:laagveen). For example, low peat can form in ponds that “fill up” with peat. “High peat” (NL: hoogveen) is formed from plants that rely entirely on rainwater for their growth and, therefore, do not make contact with groundwater. This results in a nutrient-poor peat that can grow several meters above its surroundings. Such raised bogs peat is found in both the Pleistocene grounds in the east and south and in the coastal plain.

During the Holocene, the coastal plain underwent significant development. Due to the melting of the ice cap during the Holocene, the sea level began to rise, causing the groundwater levels in the coastal areas to rise as well. This resulted in vast marshes, from which a wide strip of peat layers formed. The sea continued to advance further eastward, causing peat formation to occur progressively more to the east as well. Along the coast, the peat layers were covered with marine deposits, giving rise to so-called coastal ridges behind which clay was sedimented. Up until 4000 years ago, the coastline, along with its deposits, continued to move further inland. After this, sea level rise slowed down, but the old coastal ridges (the so called Old Dunes) remained in place.

From around the year 1000, the sea floor along the coast underwent significant changes. Initially, the sea floor gradually sloped off the coast, but due to coastal erosion, the bottom profile deepened and became steeper. The sand that became available as a result formed sand drift plains along the coast. These dunes are referred to as the Young Dunes. Where the old dunes had been spared from coastal erosion, the young dunes lie on top of them. In places where this was not the case, the young dunes lie directly on the clay and peat of the coastal plain.

The rivers deposited most of their material during a period when floods occurred more frequently than is the case today (of course there were no dikes at that time). Along the riverbanks, coarse material (sand) was first deposited, while finer material (clay) was deposited farther from the river. This led to the formation of natural levees along the banks and lower-lying floodplain areas. The natural sedimentation process results in a river channel shifting over time. Once a river abandoned its course, the levees remained visible in the landscape.