1. Probabilistic Design#

Stated as simply as possible, the term probabilistic design implies the use of probability to design something. Although this may sound complex, it is actually not much different than a deterministic approach, where values used to design something are not assumed to be random. For example, the load on a beam, or the maximum discharge expected in a river. In a typical design process, the problem and functional requirements are first defined, the system or component is evaluated and then refined (Voorendt, 2017). It is ideally an iterative process, where tradeoffs between competing requirements must be considered in order to arrive at an optimal configuration. During much of your university education you have probably learned a variety of techniques to evaluate interesting problems in your field of study; however, only towards the end of a bachelor or master program do you begin to design things and take into count information beyond what is written in a simple exam problem to make decisions. The design process is often challenging because there is no single right answer, and it turns out that incorporating probability in the design process can help.

Consider some arbitrary object–let’s call it a thingamajig–which we must design and eventually build. We would like to apply the factor of safety approach, which compares load1, \(S\), to resistance, \(R\), such that \(FS=R/S\). As long as we make sure that \(S\) is less than \(R\), or \(FS>1\), our thingamajig will never fail. We could also use the safety margin approach, where \(M=R-S\), which also quantifies the point between safe and unsafe, although here we make sure \(M>0\). These so-called limit states make the design process quite simple and is a great engineering approach for many situations, for example, if:

the values of \(R\) and \(S\) are precisely known, or the range of values is negligibly small

\(R\) and \(S\) never change (at least not over short time or length scales)

\(R\) and \(S\) are easy to measure in all locations of interest

the model used to design the thingamajig is nearly perfect

the consequence of a failure is negligible

In situations like this you can make your design decision and rest assured that there won’t be any lawyers knocking on your door in the near future because the thingamajig broke.

For many situations, however, a deterministic analysis is not wise because we cannot guarantee that our thingamajig will always survive. When \(R\) and/or \(S\) can take on a range of possible values, all of a sudden there is a chance that our thingamajig is not reliable: there is a distinct probability it may fail. Part of this book is concerned with the quantification of what is often called the failure probability, \(p_f\), for which there are many different techniques. These techniques all rely on probability theory because it allows us to quantitatively account for the following in our engineering process:

imprecise measurements

model error

randomness in some of our important design variables

risk-based design criteria and safety standards

These are just a few examples, where items 3 and 4 are the focus of the following chapters, and items 1 and 2 have already been considered elsewhere in MUDE.

Chapter Overview

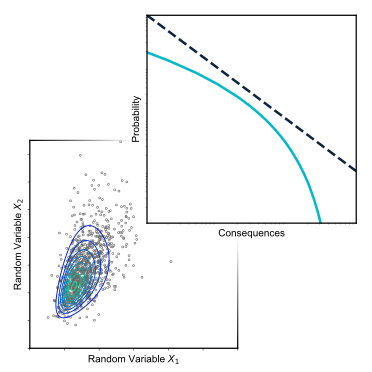

A probabilistic design is illustrated in the following sections, first with the simple cases of one random variable. Then an example with two random variables is used, which can be referred to as a bivariate case. This is more insightful than the univariate case because it allows us to consider the quantitative and qualitative influence of dependence, as well as the functional relationship between two variables and their joint probability density (e.g., union, intersection or limit-states).

The evaluation and design of a river flood protection system is used to introduce key aspects of risk and reliability, as well as the design process. A distinction is made between using probability to assess engineering components and systems (reliability analysis) and to derive design criteria (risk evaluation), which are introduced formally in later chapters after the general risk analysis framework is discussed.

The primary author for this chapter is Robert Lanzafame.

- 1

\(S\) stands for solicitation. While this letter and word are much more pedantic-sounding than simply using load, or \(L\), it is widely used in the structural engineering field, where component reliability methods were pioneered. Here we take a broader approach on the subject. Classical texts are Der Kiureghian (2022), Moss (2020) and Ditlevsen and Madsen (1996).