1.2. Two Random Variables#

The previous section illustrated how a decision for dike height, \(h_{dike}\), can take into account uncertainty in river discharge. We used a maximum allowable probability of flooding to derive the specific value of discharge, \(q_{design}\), that should be used to choose \(h_{dike}\). This was necessary because there was otherwise no way of establishing what the maximum discharge should be. The only variable considered to be random was the maximum river discharge that occurs each year. This section considers how the design process becomes more complicated when two random variables are considered (two load variables).

Distribution for \(q_1\) and \(q_2\)

On this page all calculations assume the same lognormal distribution for random variables \(q_1\) and \(q_1\), where the first and second moments of the distribution are:

For the lognorm method in scipy.stats we need to provide the parameters shape s = \(\sigma\), loc = 0 and scale = \(\exp(\mu)\) (see explanation here), in this case:

import scipy.stats as stats

s = 0.198

loc = 0.000

scale = 98.058

q_1 = stats.lognorm(s=s, loc=loc, scale=scale)

q_2 = stats.lognorm(s=s, loc=loc, scale=scale)

Discharge from Two Rivers#

In this scenario our objective for choosing \(h_{dike}\) is still the same, except now we recognize that our location on the river is downstream of a confluence of two smaller rivers. The discharge at the location of our dike is thus the sum of the dicharge from Rivers 1 and 2:

where the same rating curve applies, giving \(h_w\) as a function of \(q\). As before, acknowledging that the maximum discharge per year in each river is a random variable, we can approach the design problem in the same way: choose \(h_{dike}\) such that it retains water when \(q\) takes a value with probability of exceedance 0.01. For now, we can assume the distribution for River 1 and River 2 are the same as in the previous Section, and that they are independent.

Compared to the previous example, now there are two distributions—how do we find the design discharge and dike height?

Before presenting the correct approach, three common mistakes are illustrated.

Incorrect Approach 1#

Find the discharge in each river, \(q_1\) and \(q_2\), such that the probability of exceeding each discharge is 0.01. As in the previous section,

Why is this approach incorrect?

It considers the simultaneous occurrence of both rivers exceeding a design discharge with probability 0.01. This is a joint probability of occurrence, \(P(Q_1>q_{1,design},Q_2>q_{2,design})\), which can be evaluated with a multivariate probability distribution (or the marginal distributions in the independent case). The scenario is equivalent to observing two sixes after tossing two dice simultaneously: if the dice are fair, the probability is \(1/36\). Thus, for this incorrect case the probability \(P(Q_1>q_{1,design},Q_2>q_{2,design})\) is not 0.01, it’s actualy 0.01\(^2\)=0.0001, illustrated in the figure below.

Fig. 1.3 ‘And’ probability for Incorrect Approach 1.#

Incorrect Approach 2#

Find the discharge in each river, \(q_1\) and \(q_2\), such that the joint probability of exceeding these values is 0.01. Since the two rivers are independent, we can solve for our design probability, \(p_{design}\):

Fig. 1.4 ‘And’ probability for Incorrect Approach 2.#

Why is this approach incorrect?

It only considers one scenario!

There are infinite alternative scenarios that also result in a joint probability of exceedance of 0.01, for example, \(0.2\cdot 0.05 = 0.01\):

which results in a totally different dike height.

Fig. 1.5 Comparison of two ‘and’ probabilities for Incorrect Approach 2.#

Incorrect Approach 3#

Since the ‘and’ case didn’t work we can use the ‘or’ probability, or union! In other words: find the discharge in each river, \(q_1\) and \(q_2\), such that the probability of either of them being exceeded is 0.01.

The union probability can be found as follows:

given the assumtion of independence, the union probability is:

Solving for the case where \(P(Q_1>q_1 \cup Q_2>q_2)=0.01\) implies the exceedance probability for each river discharge is \(\sqrt{1-0.01}=\sqrt{0.99}=0.995\), thus:

Fig. 1.6 ‘Or’ probability for Incorrect Approach 3.#

Why is this approach incorrect?

As with the first two incorrect approaches, it also only considers one specific scenario! There are infinite combinations of \(Q_1\) and \(Q_2\) such that the union is 0.01.

Correct Approach#

The discharge in the main river is the sum of the discharge of its tributaries, thus it is a function of random variables which has a distribution \(f_Q(q)\). Thus we can use the distribution of \(Q\) to find the design value \(q_{design}\) directly. Unfortunately, although \(q\) is a linear combination of \(q_1\) and \(q_2\), because they are lognormally distributed we cannot find a simple analytic expression for the distribution of \(q\). However, using Monte Carlo sampling from the distributions of \(q_1\) and \(q_2\) gives:

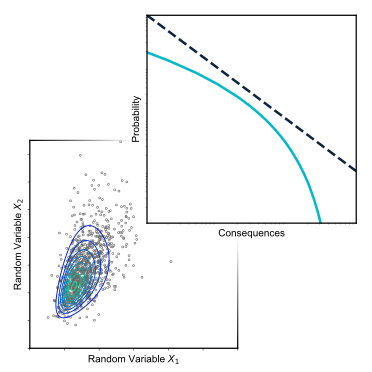

This is equivalent to integrating the joint probability distribution of \(q_1\) and \(q_2\) over the region \(\Omega\) where \(q>275\:\text{m}^3\text{/s}\), illustrated in the figure below, along with the contours of joint probability density.

Fig. 1.7 Correct approach: \(P(Q>275\:\text{m}^3\text{/s})=0.01\). Also illustrated is the region \(\Omega\) where \(q>275\:\text{m}^3\text{/s}\) and contours of joint probability density.#

Comparison of Approaches#

All four design values of \(Q\) are collected in the table below, along with the required dike height. Clearly the method of incorporating uncertainty makes a difference, as the height varies over 1 m across all options, which is a significant increase in cost for a structure that is many kilometers long.

Approach |

Design Value, \(q_{design}\) [m\(^3\)/s] |

Design Value, \(h_{dike}\) [m] |

|---|---|---|

Incorrect 1 |

310 |

8.80 |

Incorrect 2 |

252 |

7.94 |

Incorrect 3 |

326 |

9.03 |

Correct |

275 |

8.29 |

Reflections on the Simple Example#

We need to be explicit in what we are trying to evaluate. In this case, it is the distribution of a function of random variables, \(Q\).

For non-Gaussian distributions and for non-linear functions of random variables it is often not possible to get the distribution of the function of random variables analytically. Fortunately it is easy to find it numerically through sampling techniques. This will be discussed elsewhere.

The ‘and’ and ‘or’ approaches (intersection and union) are simple, but really only limited to discrete cases. As illustrated above, they cannot be used in the case of continuous random variables, or with functions of random variables because one must integrate across all possible scenarios leading to failure. Nonetheless, these approaches are extremely useful for many situations, and are the basis of system reliability problems.

The situation illustrated here is often referred to as a component reliability problem, where the ‘component’ is defined by a function of random variables. Although nothing more than a function of random variables,is nothing more than an integration over a specific region of a multivariate probability density function. Often this region describes failure of a component, which we will try to keep below an acceptable level.